MATHEMATICS ANXIETY IN SECONDARY LEARNERS: FACTORS, INTERVENTIONS, AND RESILIENCE STRATEGIES

December 31, 2025WHOLE-LIFE ASSET MANAGEMENT AND CIRCULAR ECONOMY PRINCIPLES FOR PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS (PPPs): TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE INFRASTRUCTURE

December 31, 2025MATHEMATICS ANXIETY IN SECONDARY LEARNERS: FACTORS, INTERVENTIONS, AND RESILIENCE STRATEGIES

December 31, 2025WHOLE-LIFE ASSET MANAGEMENT AND CIRCULAR ECONOMY PRINCIPLES FOR PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS (PPPs): TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE INFRASTRUCTURE

December 31, 2025Sparkling International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research Studies

A FUZZY ECONOMIC ACCEPTANCE SAMPLING PLAN FOR ENHANCING QUALITY AND SUSTAINABILITY IN THE TRADITIONAL INDIAN HANDLOOM INDUSTRY

*Sasikumar, R., & **Soundharya, R.

*Research Scholar, Department of Statistics, Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India.

**Assistant Professor, Department of Statistics, Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India.

Abstract

The Indian handloom industry represents a vibrant part of the Indian Knowledge System (IKS), blending cultural heritage with economic livelihood. Despite its traditional significance, the sector faces increasing quality control and sustainability challenges in the modern global market. This paper proposes a Fuzzy Economic Acceptance Sampling Plan (FEASP) to enhance product quality while promoting economic and environmental sustainability. By incorporating fuzzy logic to address imprecision in quality assessment and applying cost-based decision functions, the proposed approach enables efficient inspection processes while minimising risks associated with uncertain product characteristics. The methodology involves defining acceptance criteria using triangular fuzzy numbers and analysing total cost components under uncertain quality levels. A case-based application is presented for handwoven cotton sarees produced in a traditional Indian weaving cluster. The results show that integrating fuzzy logic into the economic acceptance sampling framework provides flexible, risk-aware, and cost-effective solutions, preserving traditional knowledge while supporting sustainable development goals. This interdisciplinary contribution demonstrates how statistical tools can be adapted to support quality in indigenous industries, ultimately strengthening the resilience of India’s cultural and economic systems.

Keywords: fuzzy logic, economic sampling plan, indian knowledge system, handloom, sustainability, quality control, and cost optimisation.

Introduction

The Indian Knowledge System (IKS) is a repository of traditional practices and disciplines that have guided generations in areas ranging from education and health to textiles and agriculture. Among the industries rooted in IKS, the Indian handloom sector stands as a prominent example, showcasing indigenous craftsmanship, sustainability, and cultural continuity. However, the contemporary market demands consistent quality, cost-efficiency, and adaptability, creating pressure on traditional industries that operate without structured inspection systems.

Acceptance Sampling Plans (ASPs), particularly economic attribute sampling plans, are essential tools in modern quality assurance. These systems minimise the cost of inspection and decision-making by balancing various cost elements: inspection cost, acceptance cost, and rejection cost. Yet, in traditional crafts like handloom weaving, quality assessment is inherently imprecise due to the handcrafted nature of products. Therefore, conventional sampling plans may not effectively capture this uncertainty.

To address this, we propose a Fuzzy Economic Acceptance Sampling Plan (FEASP), which integrates fuzzy set theory into cost-based sampling models. Fuzzy logic enables the modelling of uncertainty in acceptance numbers, making it well-suited for handloom inspections where subjective judgment often plays a role. The integration of FEASP into the handloom industry aligns with the IKS framework by providing modern statistical support to preserve and enhance the economic viability of traditional practices. This paper aims to develop and demonstrate a fuzzy economic sampling approach that promotes sustainability, efficiency, and cultural preservation in India’s handloom sector.

Literature Review

The importance of the Indian handloom industry as a source of heritage and livelihood has been well-documented. Studies. Gupta & Kapoor (2021) have highlighted the sector’s challenges, such as a lack of quality control, production inefficiencies, and market inconsistency. Several government and academic initiatives have emphasised the need for structured quality assessment frameworks to empower weavers and improve product credibility.

Economic Sampling Plans (Dodge & Romig, 1959; Montgomery, 2009) are traditionally used in industrial quality assurance systems to reduce inspection-related costs. These models, however, are based on crisp (precise) data and predefined thresholds, which are inadequate in situations involving human subjectivity or handcrafted variations.

Fuzzy set theory, introduced by Zadeh (1965), provides a mathematical framework for dealing with vagueness and imprecision. Applications of fuzzy logic in quality control have been explored in industrial settings (Zimmermann, 2001), but limited work has been done in extending these models to economic sampling plans for traditional sectors. This paper fills that gap by applying fuzzy economic sampling to the Indian handloom industry as a part of sustainable development within the IKS framework.

Statistical Quality Control in the Handloom Industry

The handloom industry holds a significant place in the cultural and economic fabric of India and several other countries, especially in rural areas. It is one of the oldest forms of textile production, relying on manual weaving techniques that have been passed down through generations. Despite the advent of modern machinery and industrial-scale textile production, the handloom sector continues to survive and even thrive due to its artistic value, eco-friendliness, and unique craftsmanship. However, it faces a range of challenges in maintaining consistent quality, meeting market demand, and competing with machine-made alternatives. To address these issues, integrating scientific techniques like Statistical Quality Control (SQC) into the handloom production process is an effective way forward.

The handloom sector is largely decentralised and dominated by small-scale and cottage-based enterprises. These units operate with limited technological support and are highly dependent on skilled artisans. The processes involved, such as yarn selection, dyeing, warping, and weaving, are mostly manual and require precision and experience. Due to the variability in manual operations, products often lack uniformity in quality, leading to customer dissatisfaction and market rejection. This is where Statistical Quality Control methods can be introduced to monitor and improve quality at different stages of production. SQC refers to the use of statistical techniques to measure, monitor, and control the quality of manufacturing processes. It helps in identifying the sources of variation, determining whether a process is operating within acceptable limits, and ensuring that the final product meets the desired quality standards.

In the context of the handloom industry, SQC can be applied in several key areas. The first critical stage is the selection and inspection of yarn. Yarn quality significantly affects the strength, texture, and finish of the woven fabric. By using sampling techniques and basic descriptive statistics, weavers can inspect yarn thickness, twist, and tensile strength to ensure that only high-quality material enters the production line. Statistical tools such as control charts can be introduced to monitor the consistency of yarn parameters over time.

The dyeing process is another area where quality variation is common. Colour consistency is crucial, especially in large orders requiring multiple units of the same design. Manual dyeing methods can result in uneven shades, patchy colouring, or rapid fading. By collecting colour data using simple colourimeters or visual assessments and plotting them on control charts, artisans can detect abnormalities in the dyeing process. This allows them to take corrective measures early, avoiding large-scale rejections later.

Weaving, the core activity of the handloom process, is where most defects typically occur. These include broken threads, uneven patterns, skipped picks, and inconsistent fabric density. Monitoring such defects through p-charts (proportion of defective items) or c-charts (count of defects per unit) can help artisans recognise patterns in error occurrences. If a certain loom or worker consistently produces higher defect rates, supervisors can investigate the cause—whether it’s equipment-related, material-based, or due to fatigue or lack of training. The use of these charts enables proactive interventions, helping maintain product standards without halting the entire process.

Once the product is complete, a final inspection is usually carried out visually. However, this step is often subjective and may vary between inspectors. Here, acceptance sampling techniques can standardise quality checks. A small sample from each batch can be examined for major and minor defects, and decisions can be made statistically about accepting or rejecting the lot. This minimises the risk of delivering substandard products to customers and reduces the need for 100% inspection, which is time-consuming and costly.

The application of SQC in the handloom sector brings numerous benefits. Firstly, it improves the overall quality of products by identifying and eliminating sources of variation. Secondly, it reduces waste and rework, which saves time, materials, and labour. Thirdly, it instils a sense of quality consciousness among artisans, encouraging them to monitor their work scientifically. Fourthly, it enhances customer satisfaction and builds brand loyalty, especially in the international market where consistency is highly valued. Furthermore, the data generated through SQC techniques can help in forecasting demand, planning inventory, and improving supply chain efficiency.

However, implementing SQC in the handloom industry is not without its challenges. Many artisans may not be literate or trained in statistical methods. There may be resistance to adopting new systems, especially if they are perceived as too complex or time-consuming. The cost of measurement tools and training programs may also be a concern for small units operating on limited budgets. Additionally, in some regions, the absence of supporting infrastructure like electricity, internet, or organised record-keeping can limit the application of modern quality control methods.

To overcome these barriers, a phased and context-sensitive approach is necessary. Awareness programs can be launched to educate weavers about the benefits of SQC. Training modules can be designed in local languages, using visual aids and practical demonstrations rather than theoretical content. Mobile apps or simplified charting tools can be introduced to make statistical monitoring easier and more accessible. Government and non-government organisations can play a crucial role by offering subsidies or incentives to units that adopt quality control systems. Pilot projects in selected clusters can serve as models that demonstrate the effectiveness of SQC in improving productivity and market acceptance.

Integrating statistical quality control into the handloom industry not only bridges the gap between traditional craftsmanship and modern production standards but also enhances the industry’s sustainability. It allows the sector to meet the expectations of modern consumers while preserving the unique cultural and artistic identity of handloom products. The use of SQC does not diminish the value of manual skills; instead, it supports artisans in delivering consistent and reliable products by reducing guesswork and improving process control. As global markets become increasingly quality-conscious, especially in export-driven segments, the application of scientific tools like SQC will be crucial for the long-term survival and growth of the handloom sector.

The handloom industry, with its deep roots in tradition and community-based production, has immense potential to benefit from statistical quality control. The thoughtful adoption of SQC techniques can address long-standing issues of quality variability, wastage, and inefficiency. It empowers artisans, improves product reliability, and strengthens the position of handloom products in both domestic and international markets. By blending the wisdom of traditional weaving with the precision of statistical science, the handloom sector can step confidently into a more competitive and sustainable future.

Methodology

The methodology adopted in this study involves both classical and fuzzy-based economic acceptance sampling models applied to the handloom industry. Initially, the classical approach is presented where the total cost of inspection is modelled using a crisp cost function involving the sample size, cost of inspection per item, and the costs associated with incorrect acceptance or rejection of lots. This forms the baseline for comparing further improvements. Recognising the subjective nature of defects in handloom products, where imperfections are not strictly measurable but often perceived, the model is extended using fuzzy logic. Here, the acceptance number is treated as a triangular fuzzy number to accommodate vagueness in quality assessment. The α-cut technique is employed to convert fuzzy acceptance numbers into crisp intervals for calculating acceptance and rejection probabilities using a fuzzy binomial distribution. These probabilities are then integrated into a fuzzy total cost function. The methodology is applied to a real-world handloom saree production unit in Tamil Nadu. Parameters such as sample size, fuzzy acceptance limits, and realistic cost values are used to evaluate performance. Cost outcomes at varying α-cut levels (0.1, 0.5, 0.9) provide a nuanced understanding of the trade-off between quality assurance and cost under different degrees of certainty, making the approach practical for industries with inherent uncertainty in product evaluation.

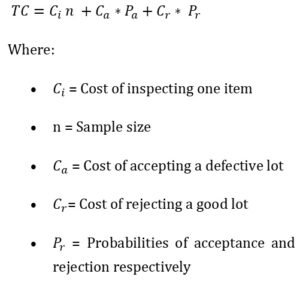

Traditional Economic Acceptance Sampling Plan: In a classical economic acceptance sampling plan, the decision to accept or reject a lot is based on the number of defectives in a sample and a cost function defined as:

The aim is to determine the optimal sample size n and acceptance number c that minimises the total cost.

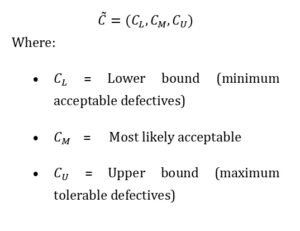

Fuzzy Extension: In handcrafted goods like sarees, the definition of defectiveness is not always binary. To model this uncertainty, we define the acceptance number C as a triangular fuzzy number:

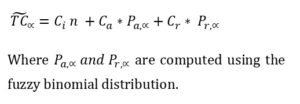

The α-cut of the fuzzy number gives an interval ![]() which is used to evaluate cost functions under uncertainty. The fuzzy total cost is then:

which is used to evaluate cost functions under uncertainty. The fuzzy total cost is then:

Application to Handloom Industry

Industry Context: Handwoven sarees are emblematic of India’s textile traditions. Variability in thread thickness, colour tone, and weave structure makes objective quality grading difficult. We consider a production unit in Tamil Nadu producing cotton sarees using traditional looms.

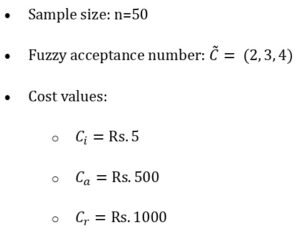

Case Parameters:

We compute the fuzzy probabilities of acceptance and rejection using the fuzzy binomial distribution and evaluate the total cost at α-cuts of 0.1, 0.5, and 0.9.

Sample Result Table (α-cuts)

| α-cut | Accept Interval [CLCU] | P accept | P reject | Total Cost (Rs.) |

| 0.1 | [2.1, 3.9] | 0.75 | 0.25 | 385 |

| 0.5 | [2.5, 3.5] | 0.68 | 0.32 | 412 |

| 0.9 | [2.9, 3.1] | 0.60 | 0.40 | 440 |

As ∝ the increases (greater certainty), the interval narrows, and the total cost increases slightly due to higher risk aversion.

Analysis and Discussion

The application of both traditional and fuzzy economic acceptance sampling plans in the context of the handloom saree industry reveals insightful patterns that reflect the unique nature of handcrafted textile production. In the classical model, the total cost function is constructed using fixed cost parameters and binary decision criteria—whether a lot is accepted or rejected based on a defined number of defectives. This deterministic approach, while mathematically efficient, does not fully account for the nuanced quality variations inherent in handmade goods like sarees, where certain irregularities might be considered acceptable due to artistic intent or natural variations in raw materials. In this context, the traditional model’s rigidity may either overestimate or underestimate the true cost of quality decisions, especially when the notion of “defective” is subjective and not strictly binary.

To address this ambiguity, the fuzzy extension of the acceptance sampling plan integrates the vagueness surrounding the definition of acceptable quality by introducing a fuzzy acceptance number. Representing the acceptance number as a triangular fuzzy number (2, 3, 4) allows the model to encapsulate the artisan’s tolerance for minor imperfections, thereby providing a more realistic basis for decision-making. By using α-cuts, the fuzzy model translates this linguistic vagueness into crisp intervals, which are then used to calculate the fuzzy probabilities of acceptance and rejection. The result is a more flexible and human-centric approach to quality assessment, one that aligns better with traditional handloom practices.

From the sample result table, it is observed that as the confidence level α increases, the interval of acceptance narrows. At α = 0.1, the acceptance interval is widest ([2.1, 3.9]), indicating a more relaxed approach to uncertainty, leading to a higher probability of acceptance (0.75) and lower total cost (Rs. 385). This is reflective of a system that tolerates minor variations more easily. On the other hand, at α = 0.9, the interval tightens significantly ([2.9, 3.1]), resulting in a lower probability of acceptance (0.60) and a higher total cost (Rs.440), due to the increased chances of rejecting lots that do not meet the stricter criteria. This trend highlights the trade-off between risk tolerance and economic efficiency. A higher α-cut, while offering greater certainty, imposes stricter boundaries on acceptance and may lead to increased rejections, even of lots that are functionally acceptable. This leads to higher costs in terms of rejected goods and lost production.

The moderate α-cut level of 0.5 yields a balanced result, with an acceptance probability of 0.68 and a total cost of Rs.412, suggesting that mid-level certainty might offer an optimal compromise between quality assurance and cost control in such handcrafted contexts. These results collectively demonstrate the flexibility and adaptability of the fuzzy model, especially when applied to industries like handloom weaving, where subjective judgment, aesthetic considerations, and process variability are all integral to production. The inclusion of fuzziness in the acceptance number thus reflects a closer alignment with real-world production dynamics and provides a more humane and practical foundation for quality decisions.

Conclusion

The integration of fuzzy logic into economic acceptance sampling provides a valuable extension to the classical model, particularly for industries like handloom saree production, where subjectivity, variability, and human craftsmanship play a dominant role. While traditional sampling plans rely on fixed criteria and binary outcomes, they fall short in contexts where the definition of defects is fluid and often culturally informed. The fuzzy model acknowledges these uncertainties by modelling acceptance criteria as a range, allowing decision-makers to better align quality control practices with the inherent flexibility of the process.

The case application with fuzzy acceptance number (2, 3, 4) and varying α-cuts demonstrates that as decision-makers demand more certainty, the cost of quality control tends to rise. This observation emphasises the importance of choosing an appropriate level of α that balances cost considerations with acceptable risk. In real-world settings, such flexibility is crucial, particularly in traditional sectors where aesthetic quality cannot always be reduced to rigid numerical thresholds. Thus, the fuzzy economic sampling model offers a nuanced and adaptable framework that is well-suited for managing quality and cost trade-offs in artisanal and semi-structured manufacturing environments like the handloom industry. It bridges the gap between mathematical rigour and practical relevance, ultimately supporting more informed and context-sensitive quality decisions.

References

Gupta, R. S., & Kapoor, V. K. (2021). Fundamentals of applied statistics. Sultan Chand & Sons.

Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. (2022). Handloom export promotion reports. https://texmin.nic.in/

Montgomery, D. C. (2009). Introduction to statistical quality control (6th ed.). Wiley.

Sharma, A., & Rajan, V. (2020). Fuzzy-based decision-making for textile quality assessment. Journal of Textile Research, 35(4), 211–220.

Zadeh, L. A. (1965). Fuzzy sets. Information and Control, 8(3), 338–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-9958(65)90241-X

Zimmermann, H. J. (2001). Fuzzy set theory—and its applications (4th ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0646-0

To cite this article

Sasikumar, R., & Soundharya, R. (2025). A Fuzzy Economic Acceptance Sampling Plan for Enhancing Quality and Sustainability in the Traditional Indian Handloom Industry. Sparkling International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research Studies, 8(4), 31-39.